Without continuous innovation, organisations sputter and die. Nonetheless, most organisations practise innovation in a haphazard manner, apparently hoping that it will happen.

Looking at the Forbes 2014 list of the World’s Most Innovative Companies, you see some of the “usual suspects” – Amazon.com, Unilever and Coca Cola. In fact, in these most successful companies, innovation is a paranoiac need. The lifeline of any unregulated organisation is its ability to continuously find opportunities for new products or services and to develop better processes to manufacture and deliver them.

New Products Are Not Always New Products

Any company that wishes to perpetuate its supremacy over a long period of time needs to have in place an on-going, aggressive and successful new product creation program. However, during our research into the subject of product innovation, we noticed that most companies concentrate their entire product innovation effort on incremental or marginal improvements to existing products. In fact, while working with companies considered to be the best at product innovation, we discovered that these companies even had difficulty defining what a new product was.

Over time, we have uncovered five categories of new product opportunities.

- New to the market. These are products that, when introduced, were unique to the market and the world. No similar products existed anywhere. Examples are 3M’s Post-It Notes, Sony’s Walkman VCR, and Apple’s iPad.

- New to us. When Panasonic introduced its own version of the VCR, it was not new to the market since Sony had done it before. But it was new to Panasonic.

- Product extensions. In this category, we find two types: incremental and quantum leap. An example of an incremental extension is 3M’s adaptation of the original Post-It Notes into larger sizes, shapes, with colours and adaptations like flags, tabs and dispensers. Boeing’s announcement of a supersonic passenger jet is a quantum leap extension. The technology required is a significant step beyond making its standard passenger jets.

- New customers. This category applies to the introduction of current products to new customers, such as e-readers tapping into the textbook market.

- New markets. This category applies to the introduction of current products to new market segments or new geographic areas, such as Subway’s steady global expansion.

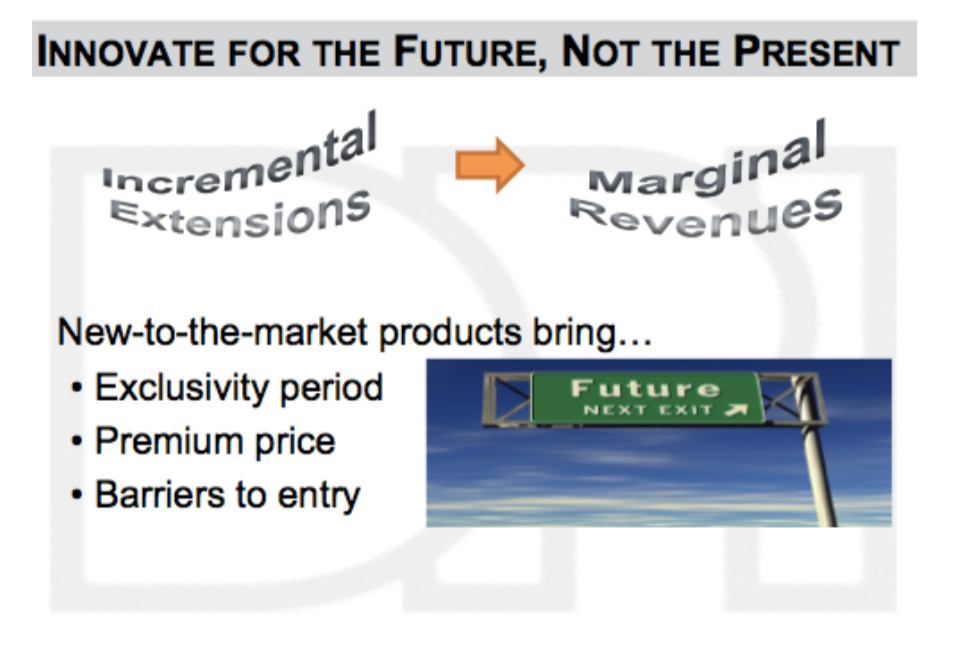

The next area we investigated was: In which category did they invest most of their resources? Guess what over 200 companies answered? Right: product extensions – of the incremental type. The food and packaged goods industries, for example, have perfected the art of “new and improved” products in different colours and sizes. Unfortunately, incremental extensions only bring incremental revenues. Only new-to-the- market products create new revenue streams.

The 4 deadly sins that kill strategic product innovation

Since new-to-the-market products are the essence of strategic supremacy, we then set out to identify the obstacles that caused companies to spend almost all of their time, money, and energy on product extensions at the expense of new-to-the-market products. Our discovery? Most companies committed one or more of four “sins” that killed new product creation and led to a company’s loss of supremacy over its competitors. Unfortunately, all four were self-inflicted wounds.

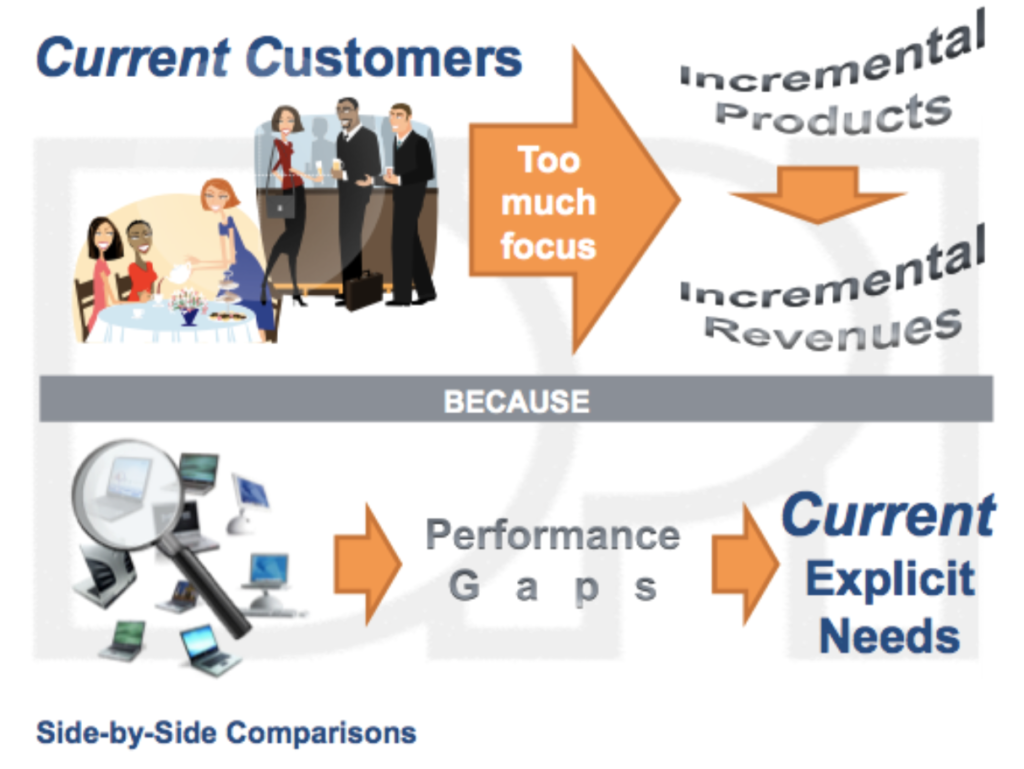

Sin 1: Too Much Focus on Current Customers. Who do most books on product innovation tell you to consult in order to get inspiration for new products? The obvious answer: your customers. Wrong, dead wrong! If a company focuses its entire effort on current customers as a source for new products, it will always end up with incremental products. The reason is very simple. Current customers are very good at telling you what is wrong with your current product. Naturally, you go back to the factory, tweak the product a little, and come back with an incremental improvement. And the pattern is set and keeps repeating itself.

You cannot depend on current customers for your new product ideas because they are not very competent at telling you what they will need in the future. Not one of 3M’s millions of customers ever asked 3M for Post-it Notes. Not one of Sony’s millions of customers ever asked for a Diskman or a VCR. No one on this planet ever asked Steve Jobs for an Apple computer or an iPod or an iPad. And the list goes on. These are all products that originated in the minds of the creator, not the recipient. Jobs, perhaps the best and most influential innovator of recent times said, “It’s not the customer’s job to know what they want.”

You cannot depend on current customers for your new product ideas because they are not very competent at telling you what they will need in the future. Not one of 3M’s millions of customers ever asked 3M for Post-it Notes. Not one of Sony’s millions of customers ever asked for a Diskman or a VCR. No one on this planet ever asked Steve Jobs for an Apple computer or an iPod or an iPad. And the list goes on. These are all products that originated in the minds of the creator, not the recipient. Jobs, perhaps the best and most influential innovator of recent times said, “It’s not the customer’s job to know what they want.”

In order to breed competitive supremacy and create new revenue streams, it is imperative to concentrate a company’s product innovation resources on new-to-the-market products.

These are products that satisfy future implicit needs that you have identified and that your customers cannot articulate to you today. In this manner, the result will be products that will allow you to change the game and perpetuate your supremacy. If you know where to look, identifying changing needs is not as hard or miraculous as it may seem.

Sin 2: Protect the “Cash Cow” Mentality. Every company, over time, has products that become cash cows. Never worship at the altar of the cash cow. You will lose your supremacy. Here are some classic examples.

IBM’s cash cow, as we all know, had been its mainframes, once the workhorses of the computing industry. In 1968, IBM invented the first microchip, with more processing capacity than its smaller mainframes. A small computer prototype, powered by this chip, was built and could have been the first PC the world saw. IBM, however, made a deliberate decision not to introduce that chip, because it could foresee the devastation it might have on its mainframe business. In 1994, 26 years later and maybe 26 years too late, IBM finally introduced the chip under the name PowerPC. Meanwhile, IBM lost the opportunity to be the powerhouse in the consumer market that it was in the business market. In 2005, IBM eventually admitted defeat in the PC space and sold out this arm to Lenovo.

The same happened at Xerox. The company worshipped so diligently at the altar of large copiers that it did not see the advent of a stealth competitor – Canon – with small copiers. Furthermore, it failed to capitalize on unique inventions that were developed in its Silicon Valley laboratories, such as the mouse and inkjet printers, both used successfully by Apple later.

General Motors’ fixation on large, gas-guzzling cars of questionable quality caused it to fail to foresee the entry of Toyota and Honda into the U.S. market with small, high-quality cars that reduced GM to half the company it used to be.

We are not suggesting that you slaughter your cash cows on a whim. Singapore Airline’s cash cow is business class travellers and that is not going to change anytime soon. However, savvy competitors will attack your defences and sooner or later they will be breached. New technologies can never be put back into Pandora’s Box. So, if someone is going to destroy you cash cow, it might as well be you.

Sin 3: The Mature Market Syndrome. “Our industry is mature. There is no more growth in these markets.” Many people would claim that the reason products become generic, prices come down to the lowest levels, and growth stops is that the “market is mature.” Mature markets, in our view, are a myth.

Consider some examples. Who would have thought years ago that people would pay £150 for a pair of shoes? Running shoes at that! After all, everyone had a pair of £5 pumps, and the market was mature. Then along came Nike and Reebok, and the “mature market” exploded.

Who would have believed a few years ago that anyone would pay £3 for a cup of coffee? Yet Starbucks revolutionized the coffee business by introducing unique products and marketing in a “mature” industry dominated by Dunkin’ Donuts for decades. Dunkin’s Donuts had mastered the perfect 50-cent “bottomless” cup in the US. A cup of coffee, after all, was just a cup of coffee.

Two CEOs who have based their success on debunking the notion of “mature” markets are Jack Welch, General Electric’s famous ex-CEO, and Lawrence Bossidy, formerly CEO of Allied Signal. Jack Welch preaches that “mature markets are a state of mind,” while Bossidy says, “There is no such thing as a mature market. What we need are mature executives who can make markets grow.”

Sin 4: The Commodity Product Fallacy. “We’re in the commodity business” is another mind-set that can bring down a company’s supremacy. This is also a state of mind. Products become commodities when management convinces itself that they are. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you believe your product is a commodity, then so will your customers. If you believe your product is a commodity then investment in R&D will be cut back to zero and the focus instead shifts to production efficiency, leading to differentiation on price, the very definition of a commodity.

Kevin Surace is a serial entrepreneur, and former InfoTech executive, who established Serious Energy, a supplier of the new iWindow, based on a number of technical innovations to glass, a product that has been around for centuries. He put it this way, “Somehow buildings, which is a $5 trillion worldwide industry, was left to die. Everyone said it’s a commodity business. I said it is a commodity business because nobody went there to do anything about it. So they keep making the old [building material] products that they’ve made for a hundred years and they’ve commoditised themselves. I know companies that have not done a single bit of R&D for the last 30 years. It just became overhead. Now, they wouldn’t know how to develop a new product. The last person to do so died 30 years ago!”

Many food and drink manufacturers have leveraged “cash rich, time poor” and other consumer trends to turn old commodities into high value items. Take the humble lettuce, which after a simple clean cut and attractive packaging can see its sales value soar. With is its super- convenient Nespresso machine, which dispenses fresh espresso coffee at a touch of a button from individually sealed capsules, Nestle has successfully persuaded millions of consumers to pay around three times the price of regular ground coffee (on a pound for pound basis.)

Then there is the “mother” of all commodities – water. Yet, look at what the French did with water. They have mastered the marketing of this mundane commodity by branding it under a variety of names such as Vitel, Evian, and Perrier. Knowing that people are becoming more concerned about the quality of the water they drink, they began to market bottled water at exorbitant process. This concept was immediately successful even in places where tap water is excellent and essentially free. Through brilliant marketing, they made water “trendy,” creating “designer brands,” and they charged even more.

New-to-the-market products breed supremacy

Apple, 3M, Amazon, Microsoft, Johnson & Johnson, Caterpillar, and many others maintain their control of the sandbox not by introducing “me-too” products but rather by focusing their resources on the creation of new-to-the-market products. These have three inherent characteristics that contribute to breeding supremacy over their competitors:

A period of exclusivity. When you are the only product in the market, you are the only one.

Ability to charge premium prices. During this period of exclusivity, you can obtain premium prices, as opposed to me-too products, where every transaction comes down to haggling over price.

Ability to build in barriers. Being first to the market allows you to build in barriers that make it very difficult for competitors to gain entry into your game. Apple’s pursuit of Samsung through patents and other intellectual property is a good example.

After all, that’s what supremacy is all about: changing the game and creating the rules to which competitors who wish to play your game must submit.

The Strategic Product Innovation Process

Strategic supremacy is highly dependent on an organisation’s ability to create and bring to market new products more often and more quickly than its competitors. We view new product creation as the fuel of corporate longevity. The secret of these product innovator superstars is a deliberate process that causes product innovation. This systematic process is known and used by everyone in the company.

Observing this phenomenon, we at DPI went on to codify this process being practiced implicitly at these kinds of companies. The result is a unique process called “Strategic Product Innovation,” which makes new product creation a learnable, repeatable process. This process can be used by any organisation to create and commercialise new-to- market products, to generate new revenue streams, allowing the company to grow faster than its competitors. This conscious, repeatable, business practice consists of the following four steps:

Creation. Carefully monitor the 10 sources of change in your business environment from which you can create a broad range of opportunities for new-to-the-market products.

Assessment. Measure the new product opportunities in terms of costs, benefits, strategic fit, and difficulty of implementation. These criteria will let you know which opportunities should be pursued further – and which should be abandoned.

Development. Once a commitment is made, anticipate the critical factors that will cause the new product to succeed or fail.

Pursuit. Develop a specific implementation plan that promotes success and avoids failure.